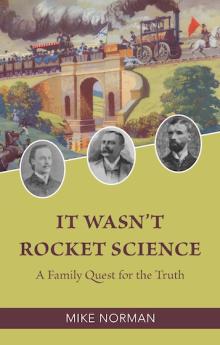

www.timothyhackworth.com

Read a Short Extract

Chapter 1 Coming to America

Baltimore, Wednesday 16th November 1892

The building on the corner of Baltimore Street and Calvert was not intended to be ignored or overlooked. Five storeys of granite and brickwork were topped by an ornamented mansard roof. Its presence there reflected the substance of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad itself. It stood out from the crowd. Momentarily a man paused by the building, looking up at the colonnaded battlements of the railway company’s head office. Timothy Hackworth Young, to give him the full name by which he had been christened, wondered whether the person who had invited him here could do what he said. Major Joseph G Pangborn had asked him to visit, eager to hear what more could be contributed to honour the inventiveness of a locomotive pioneer. He wondered how much the man really knew of his grandfather, Timothy Hackworth, the engine builder of Shildon. Wondered how this man could do what the Hackworth family, over the years, had found themselves unable.

A letter sent directly from the office of C K Lord, Third Vice President of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company, was the first contact the Hackworth family had with the railroad company. It had been received by his Aunt Prudence in England – aunty Pru as she was known inside the family. Vice President Charles Lord sought the loan of any significant items or material about Timothy Hackworth still in possession of the family. His letter had been followed all too promptly by further correspondence from Major Pangborn, to which his aunt replied with some caution.

However, Timothy Hackworth Young knew that in America, his adopted country, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad stood head and shoulders above any other in promoting the railway. He had been more than happy to accept an invitation from the ‘B&O’ to come to Baltimore. This was the 1890s. Railways were big business. Their plan was to put on the biggest railroad exhibition the world had ever seen.

The Columbian Exposition was going to be used to celebrate the birth of the railway, the marvels of the locomotives and the pioneers who overcame formidable challenges to forge a new era of transport. The B&O intended to show the world how this modern magic carpet was unleashed, set free and shaped by truly exceptional men. He was here because they wanted to talk over how they could best make a showing of the work of Timothy Hackworth. Make him, too, stand out from the crowd. That idea stoked his imagination, and he had thrown Aunt Pru’s caution to the winds.

He continued to look up at the heights of the building as he briefly tapped his jacket pocket. Major Pangborn’s letter of invitation was safely there. Reassured, he dropped his gaze to the building’s entrance and back to earth. Timothy Hackworth Young walked into the head office of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company and made himself known, never for a minute realising how significantly it would change the direction of his life. His eyes were about to be opened to the singular accomplishments of his grandfather. Endeavours, too often attributed to the exploits of others who were around him at the time of the Stockton & Darlington Railway, were due to be recast.

*******************

The name on the mahogany door simply said J G PANGBORN. The man who opened it to him was shorter than he expected, had a friendly smile on a well rounded face and sported the neatest moustache he had seen in a long while.

‘Timothy, isn’t it?’

Timothy looked past the welcome he was proffered and couldn’t help staring straight into the space that was Pangborn’s office. It was dense with books, with folders, with paperwork. Shelves that went from floor to ceiling were full. The large desk had numerous piles of papers on it. And there was carpet on the floor.

He must have hesitated at the sight. So much so, the man he’d come to see added ‘Come in’ and, when his visitor did, only then completing his greeting.

‘I can hardly believe that we actually have our own railroad man from Hackworth stock here in America. So very pleased you made it.’

Timothy looked around him. Looked at the many photos of Pangborn that adorned the wall of this office; Major Pangborn pictured with dignitaries, Major Pangborn pictured on board trains that bore the distinctive ‘B&O’ mark of the company, Major Pangborn pictured with the president of the company, Major Pangborn pictured in the construction sheds with newly completed locomotives. He struggled to take it all in. Major Pangborn clearly made up in status for any shortfall he might have in stature.

It was all a far cry from the workaday office Timothy normally shared with other foremen. Men he worked alongside in the locomotive sheds of the railroad company for which he worked in Chicago.

‘Do take a chair, sit down. Make yourself comfortable, we want you to feel at home. We have much to talk about.’

He didn’t know if he could actually feel at home in these surroundings. This was a far cry from the railroad world that was his lot. His job was to make sure the company locomotives were inspected, always kept up to scratch and, when needed, repaired. Now he had been taken up to the dizzy heights of the management floors of the prestigious Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company, and in an elevator. If he owned up to how he felt right now, he was more than a touch overwhelmed. He could well believe that an exhibition being organised by someone with this patronage would be something special, and he was here because it was going to include his grandfather. That thought did nothing to clear the heady feeling.

‘Well, Timothy Hackworth Young. How does it feel to be part of a family that put the locomotive back on the rails when it nearly fell off?’

Pangborn’s words barely registered with him but he knew they needed a response. He struggled to find the right words and could only manage to say, ‘I’ve always been proud of the Hackworth family but when my grandfather had his locomotive works was a long time ago.’

Pangborn carried on talking as he walked his guest to a chair nearby to his desk. ‘We watched closely, visited, saw for ourselves what was developing in England. Make no mistake. Your grandfather was one of the pioneers. Making trains that worked where others failed. Amongst all the trials and triumphs that it took, I know my work would not be complete without Timothy Hackworth being given his due place.’

He sat down in the grand captain’s chair behind his desk, and opened the first of the several folders in front of him. He leant forward, making sure he had Timothy’s attention, then set the scene for this encounter.

‘Let me explain,’ he said in a most convivial tone ‘the one thing that is driving us all, and by all I mean the world at large, is the railroad and it’s the locomotive that brings it to life. Columbus found this new world of the Americas by pushing forward what his ships could do and where they could go. What better way could there be for us to celebrate the 400 year anniversary than showing the rest of the world our means of travel, our transportation of delight.’ He paused. ‘You’ve seen the book – ‘On Picturesque B&O’ – well we persuaded the committee that the most fitting tribute would be to make ‘Transportation’ a major focus for the Columbian Exposition. Of course there has to be the showing of the latest wonders from all the countries of the world but Columbus needs a special showing. And who better to do that than the best railroad company in America. Certainly the first…’

Timothy allowed himself a slight grin at that. Every railroad man thought he worked for the ‘best railroad company’ but this probably wasn’t the moment to challenge Major Pangborn.

‘Certainly the first…and our Vice-President, Mr Lord, and myself elbowed our way to the top of the queue. Our proposition was that we should have, for the very first time in the world, a section of a World Fair devoted to Transportation. We, that is the directors of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company, want to show how we have come to this watershed time in our nation. Not just show off what we now have. We want to tell the story of how others have got us to this moment.’

Pangborn couldn’t be said to be lacking in ambition for the company he worked for, and what he said rang true. It also neatly brought together the ambitions of the B&O to set itself foremost in the eyes of all who visited the exposition with the ambitions of a newly settled America, the free and united states of America, to take its place in the world.

Timothy bought it, just as others had. The Columbian Exposition would be a truly historic event. Transportation, railroads, locomotives, all being used as the focus to put down a marker for the United States of America in front of a world-wide audience. He couldn’t imagine what that would take, or how it could be done, or how his grandfather’s work would fit in.

Major Pangborn had no such shortage of imagination, or plans and facts.

‘England was the cradle in which the baby was first laid and nurtured. It took a lot of trial and error. Some folk think that your decisive moment could be traced to the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, to one man – George Stephenson, and to one locomotive – Rocket. We know better.’

Rainhill, Liverpool, Saturday, October 10, 1829

The crowds in the grandstands, the men of science, businessmen and engineers from around the globe had come for yet another day to witness the most exciting event in the whole year. The Locomotive Trial of the century – finding a locomotive worthy of serving the new railway link between two powerful centres of trade. Today, day four of the trial, George Stephenson, Superintendent of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, had been watching how ‘Novelty’, the London locomotive entry, was performing. Saw how well it had made time against the clock. He had become seriously concerned. That was until an official brought him the news. ‘It looks like we’re going to have to call a halt for today, George. Some repairs need to be done to the loco before they can carry on.’

George Stephenson had seen the reaction of the crowds and realised how eager they were to see the competing locomotives in action. The months of planning for this event had played into the public appetite for a spectacle. Here was a moment to put his competitors in the shade now that technical issues had delayed running the trial of Novelty. This was not an opportunity to be lost. ‘Look at the crowds,’ he responded. ‘You canna turn them away now. We’d best do something.’

He had already completed his own timed runs two days before – comfortably meeting the requirements set by the directors of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway – the L&MR as it became known. He’d met all the conditions. So he ought to; he’d helped set them. He had made sure his son, Robert Stephenson, had enough time to design, build and test the new locomotive; the trial was to be run over a sufficiently short distance that his locomotives would not run out of steam; he’d had a hand in setting the rules – even in the resetting them when the strength of the competition was apparent. Rocket was the entry George Stephenson had made jointly with Booth, the Secretary of the L&MR; joined him as a partner as he’d done in a piecemeal fashion with others before. He had fought long and hard to get to this stage. Even so, the competition was turning out to be stronger than he had expected. Too much was at stake, and it had begun to look too close to call. He had to win. Rainhill was no place for any more setbacks. Time to forget about rules.

George Stephenson grabbed one of the judges’ bright green flags. He waved it on high to catch the attention of the crowd who had been waiting all the morning to see Novelty showing its paces. The crowds were still waiting to see something of note. He could give them such a performance that even the few dissenting directors on the L&MR Board would not be able to doubt his supremacy. He was decided, as he told the official in no uncertain terms, ‘Let’s give them a show – unhitch all the wagons and I’ll give Rocket its head. Take off the tender as well. Get down to racing trim.’

The iron horse that was Rocket was pushed up to the starting point, well in sight of the grandstand. George Stephenson stood proudly alongside. His driver in place, Rocket was soon snorting and impatient to show its paces. George Stephenson shouted to the driver, ‘They'll see a one today. Give it everything we’ve got. Get steam up. Don’t worry about going high with the pressure. We’re not under starter’s orders now…’

All eyes in the stand were now drawn to the tall man standing beside the locomotive, waiting on as it got steam up. The bright colours of Rocket had it decked out as well as any of the stagecoaches the locomotive would have to compete with; deliberately casting a lasting impression in the minds of the spectators of the horse drawn stagecoach struggling to match the locomotive. He ought to have had someone blow a blast of ‘Tally ho’ on a long coach-horn to signal the start. He’d missed a trick there. Shame that John Rastrick, one of the judges and a man who had doubted the wisdom of the decision to use locomotives for the L&MR, wasn’t still there to see this run. When he judged the moment right, he stopped waving the green flag, let it drop and shouted to the driver, ‘Ha'way man. Let her go and don't slack the reins’.

Rocket with George Stephenson on board flew away. The oohs of astonishment from a 1000 spectators told their own story. The speed built up and continued to build as the mile-and-a-half marker approached. The locomotive powered its way forward, faster by far than a team of horses could speed a stagecoach, no matter how fleet of foot they were or how much they were urged on. By his watch, it had taken around three-and-a-half minutes to cover the distance between the marker posts. He reckoned Rocket might have touched 30mph before the driver released steam pressure, more than double the speed it had made under full load in the trial. He’d ask him what pressure he’d let it reach to make that speed – sure in the knowledge that no matter what pressure that turned out to be, it would be below that certified by his son for the locomotive. An exploding boiler, one that would take the life of his driver and sink his ambitions, was a risk to be avoided.

He thought the crowd could be heard applauding, and for them he ran Rocket back and forward over the trial distance again. He’d set the standard, far better than he could have hoped for; better still than it would have been under the scrutiny of the judges. Enough had been done for Rocket to take a rest before any other locomotive took to the rails.

Next time the crowds saw his two main competitors, Novelty and Sans Pareil, they would each be hauling a full load of wagons as specified in the trial conditions. After all that the spectators had just seen, no matter how well they performed it would appear they were slower. Much slower. Rocket looked good, performed well and, for the first time for a long while, George Stephenson felt good about the outcome. Today, he had shown Rocket as the most powerful engine in the trial. Any result that put either of the other contenders ahead of Rocket could be challenged – people believed the evidence of their eyes. It was in the bag.

Getting the story straight...

‘…We know better.’

Those words from Major Pangborn registered with Timothy Hackworth Young. They certainly made him sit up and listen. Not much was said within the family about Rainhill. Only that grandfather had taken on too much, was not able to give the competition and his entry as much attention as it had needed. ‘Sans Pareil’, supposedly without equal, had not lived up to its name. He’d been left humbled by the outcome and smarting from the result.

Though Pangborn’s words ensured he had Timothy Hackworth Young’s full attention, they were nothing as compared to what followed. ‘We were as interested as the rest of the railroad companies in the outcome of the battle for supremacy between the locomotive and the established use of fixed steam engines and ropes. Our railroad was underway and we were still keeping to real horse power. Rainhill promised to be a spectacle and a glimpse of the future that no one wanted to miss.’

Timothy knew all about the American railroad companies and their interest in what was happening in England in the early days. There were some among the people he worked with at the Chicago, Milwaukee & St Paul Railroad whose fathers, uncles, cousins had been there at the start of the American experience. Before that, engineers and directors of the Baltimore and Ohio would regularly visit England to keep a check on developments and disasters. The many files he could see on Pangborn’s desk testified to that interest. One folder, clearly marked ‘Rainhill’, lay on top of another marked ‘Rocket’. Timothy wondered whether the Major intentionally kept his life similarly well ordered.

Pangborn opened the top folder, flicking through papers, sketches and plans until he came to one report in particular. Timothy waited patiently until Pangborn looked up. When he did, he looked Timothy directly in the eye before he spoke.

‘We discovered that John Rastrick, one of the officials, doubted the basis of the Rainhill trial and the value of those results but he had been asked to judge according to the criteria of the directors of the railway – so the award went to the locomotive submitted jointly by their own company secretary, Henry Booth, their own superintendent, George Stephenson, and very conveniently built by Robert Stephenson, his son.’

Timothy started aback, but Pangborn hardly noticed.

‘You would have thought the directors would have asked Rastrick to help set the conditions for the trial. He was a respected engineer. They had already called on him to make an independent report on the viability of locomotive power for their railway. That had been prompted when it was heard abroad that the pioneering Stockton & Darlington Railway was thinking of returning to good old dependable horse power. He could have devised a suitable test for the Liverpool & Manchester railway – a more practical trial, less showboating. He deserved to make more of a contribution than just being a timekeeper and he thought the way the different load to be carried by each locomotive was calculated made no sense.’

Timothy tried to imagine what it must have been like having to grapple with the burgeoning developments in locomotive engineering practice. Science was running well behind, behind a smokescreen of complex formulae and experiments. The Rainhill Trial might have stretched over the best part of a week but what criteria would have been chosen at the time?

Pangborn spoke with the confidence of hindsight. ‘Rastrick was right. It didn’t prove anything worthwhile. Not like the trial we set out when Baltimore & Ohio wanted to find the best design for our locomotive on our land routes. We took several months performance with real loads for each contestant. Besides which, in design we had to virtually start over. Too many twists and turns on our railroads as they followed the lie of the land. Too easy for your locomotives to leave the tracks – too many disasters. And there was much attention given in England to restricting the radius of curves in your railroad lines…’

Timothy was completely nonplussed by the news about Rastrick. ‘But didn’t the Rainhill trial turn out to be a no-contest for Rocket?’

Pangborn had all the details at his finger tips. There were reports aplenty for him to draw on: the newspapers at the time, the journals and a report made by the respected B&O engineer, Winnan, on his return to Baltimore.

‘Your grandfather’s locomotive Sans Pareil had a faulty cylinder, blew up and could not complete enough trips running backwards and forwards on the track. The other contender, Novelty, failed at first attempt. Failed again after being repaired. Stephenson and Rocket were left as the only contenders to complete the trial and meet the requirements.’

Pangborn settled back into the arms of his chair. Time for this Hackworth family member to be told the truth.

‘Except, Sans Pareil had Rocket beaten for speed – and that was with having to haul a heavier load – and the much lighter Novelty looked as though it would have done too. So not much of a trial really.’

He paused for effect.

‘The real decider about whether the locomotive was a commercially viable proposition had already taken place at Darlington with your grandfather’s ‘Royal George’ – now that was a gamechanger and a watershed event.

Pangborn closed the ‘Rainhill’ folder and, as if to make his point, first slapped it shut with his hand, then he moved it away to one side of his desk.

‘And the locomotive that the Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened with was not Rocket but a virtual redesign - which crucially then included one of your grandfather’s inventions – and that was what was needed for a version of Rocket to be made powerful enough to operate in the conditions of the actual railroad. The whole Rainhill trial turned out to be no more than a George Stephenson benefit match.’

Timothy was unsure how to respond to the evident endorsement from this senior figure in the B&O. Very pleasing, but where was this leading him?

Pangborn knew what he wanted of Hackworth’s descendant, even if the man himself had no idea. ‘In terms of the history of the locomotive, Rainhill was little more than a sideshow and our contribution to the Columbian Exposition is planned to be considerably more than that. We are putting eleven acres of exhibits on display. Our part in the celebration of the whole idea of transportation….covering the shaping of the locomotive over the years. From the early beginnings right up to the time of the B&O, when we opened the first commercial railroad in America. A most dramatic and historic exhibition. A window into the world of those early pioneers and how what they gave us has become the power that moves the world.’

Timothy Hackworth Young’s head was momentarily in a spin. The enormity of the challenge that Pangborn was intending to meet was beyond anything even he as a locomotive man could imagine. Eleven acres of exhibits!

Pangborn’s words filtered through those thoughts.

‘We’d like you to help us get the Hackworth part of that story right.’

The possibilities for settling the reputation of Timothy Hackworth in such an exhibition, defining his place in the history of the locomotive, was exciting. It was also an overwhelmingly daunting prospect.

Copyright © Mike Norman March 2021