Read a Short Extract

2

.

.

Michael let his stomach settle for a moment and arched his back to look out of the car’s rear window. His eyes settled on the cheap corner-store grocery a little further down the street. It was typical of the stores Italian immigrants were setting up all over the city – single-storied, a shop in the front, living quarters in the back, a yard for deliveries at the rear, and a sheet-metal sign teetering above the whole jerry-built mess, proudly displaying the owner’s name. Michael sighed and rubbed his face, running his fingers along the scars that pitted his cheeks.

Outside the store, among the carriages from the Police Department and the Coroner’s Office, a mob had gathered – Italian locals that a cordon of patrolmen was half-heartedly holding back. Michael could tell it wasn’t the usual kind of crowd that always seemed to materialise at grisly crime scenes – the passers-by, the neighbours, the reporters, the street-corner habitués with nothing better to do. This crowd hadn’t gathered out of macabre curiosity. It was there because it was scared, and Michael’s heart tightened at the sight of it. From what he knew about human nature, it didn’t take much for fearful mobs to turn violent.

‘Into the madding crowd,’ he mumbled to himself.

‘Say what?’ Perez asked, glancing up from the notebook with a frown and a dart of his eyes in the rearview mirror. But Michael had already opened the passenger-side door, flipping his homburg onto his head and stepped out into the street.

He strode towards the far end of the cordon, hoping to avoid being noticed by taking the longer route, but Michael was a lurching type, singular and easy to spot. He was a head taller than most other men, with gangly, awkward limbs, and a face razed red and bumpy by smallpox. As he approached the cordon, he pulled the homburg low, but a beady-eyed reporter happened to turn his way at just the wrong time. Michael saw him nudge one of his colleagues and whisper, and in an instant the crowd erupted. Cameras swung toward him and a riot of flashbulbs strobed and popped, sending little clouds of soot into the air that mottled the fog. The paper men shouted his name and bellowed out questions. Angry Italian phrases flew his way. He carried on pushing past the throng, and after a few seconds of jostling he made it to the cordon and through to the other side. He nodded hello to a few of the patrolmen that he recognised, stony-faced, annoyed-looking men, none of whom bothered to respond. A young, earnest beat cop in a starched blue uniform trotted down the front steps to greet him.

‘Morning, sir. The victims are this way,’ said the beat cop, a greenhorn called Dawson, freshly returned from the war and eager to prove his worth. He held his hand up to the storefront with a smile, and Michael thought there was something of the maitre d’ about the gesture. He nodded his thanks and Dawson led him up the front steps and into the dim interior of the grocery.

The store was lined on all sides with neat pinewood shelves crammed with tins of fish, meat and assorted Italian delicacies that Michael had never heard of. Drums of olive oil were piled high along one wall, and festooned from the rafters were upturned bunches of dried oregano that to Michael’s mind lent the store a grotto-like air.

At the far end was a glass counter filled with breads and foul-smelling cheeses, and a Dutch meat-slicer, its cranks and disc-blade gleaming, a leg of pork still lying in the tray. The cash register stood next to it, and as Michael expected, it was completely undamaged. Beyond it was the door into the domestic part of the building. They approached, and Dawson held up his hand again. Michael, unsure of what to make of the boy, nodded and smiled. He took off his homburg and stepped through the door.

The living room was cramped, illuminated by a greasy light, and made smaller by the officials drudging away in it. Two patrolmen were taking an inventory, a doctor from the Coroner’s Office wqs bent over one of the bodies, and a photographer, a Frenchman with a portrait studio in Milneburg, readied a new roll of nitrate for his camera.

Michael inspected the room – a dark wood table and a sideboard filled most of the space, a window looked out onto the side of the neighbours’ house, and at the back a door led into the kitchen. None of the furniture had been upset or overturned, and a gospel book still lay at one end of the table. The walls were covered in floral wallpaper, yellowing and ancient and spotted with mold. Photographs of somber old Siciliains competed for wall space with an accumulation of cheap religious images – crucifixes, Madonnas, postcards of cathedrals and pilgrimage sites. In the space that led to the kitchen were the bodies of the two victims, splayed out on the linoleum floor in a pool of dark, resinous blood.

Michael crossed the room and knelt next to the bodies. The wife was short and plump, with aged skin and salt-colored hair. Dried blood had glued her nightdress to the rolls of fat around her midriff, marking out the curve of her figure. Michael could make nothing of her face, which had been so viciously attacked with a sharp object that it resembled less a human head than some kind of crater, around the lip of which a handful of flies buzzed frenetically.

The husband was slumped by the window. Most of Michael’s view was obscured by the doctor who was still examining the body, but he could see the man had wounds similar to his wife’s. His right arm was outstretched and pointed towards the sideboard, whose lower drawers were streaked with finger-wide lines of blood.

Michael shook his head and took a last, sorry look at the two corpses. He had learnt it was best not to dwell on the savagery his job confronted him with, so he crossed himself, a token gesture that somehow helped insulate him from it all, then he stood and stretched the tension out of his knees. Behind him the photographer took a snap and the flashbulbs popped in the stillness.

Michael wiped the blood from the soles of his Florsheims onto an already ruined Persian rug, stepped over the wife’s body and entered the kitchen. An axe had been left by a cupboard, propped up on its rough-hewn handle. Michael noticed fragments of bone speckled along the blood-encrusted blade.

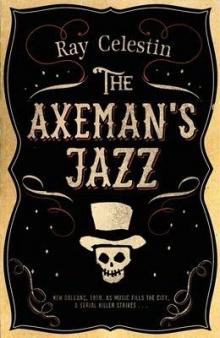

Copyright © Ray Celestin 2014